Why does politics feel crazy these days, and what can we do about it?

Last year, I facilitated a year-long conversation called Between Americans. The 24 participants—half red and half blue—had signed up hoping to achieve connection and understanding across the political schism. By the end of the year, most hadn’t achieved what they’d hoped for.

Certainly, I’d facilitate the conversation differently now. Other similar projects, both online and in person, seem to be achieving dialogue more successfully than we had. But the experiment succeeded in one regard: it revealed truths about our national disconnection that couldn’t be blamed on other people.

(For a more personal version of this essay, check out “Beneath partisan politics“, edited by Anne Focke. She wrangled a version of this essay that I’d all but given up on.)

This is a three-part essay. Click to jump to:

Part 1: Why does polarization matter?

Part 2: Why are we polarized?

Part 3: How can we heal our polarized society?

Part 1: The Polarization that Isolates Us

Over the last two decades, Americans have become significantly more partisan. Even locally, we seem to be losing our ability to disagree constructively.

Disagreement is a good thing. The polarization that isolates us from each other is a problem. Here’s why.

1. Polarization cuts off productive dissonance.

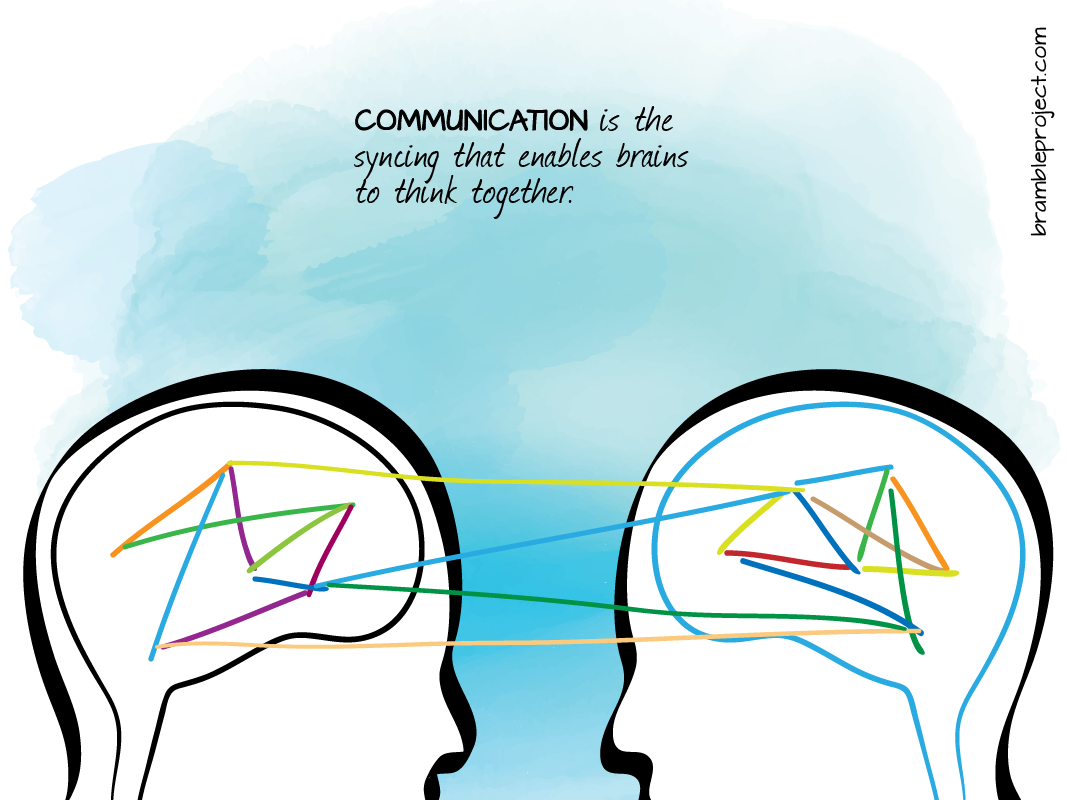

Research shows that a group’s collective intelligence—its ability to solve problems—is not strongly correlated with how smart group members are. What does matter is how often group members talk, how evenly they spread the conversation around, and how well group members can perceive each other’s emotions.

When we communicate, our “ideas have sex”, as journalist Matt Ridley would say. The outcome is not necessarily one idea winning over the other. Rather, clashing viewpoints can generate new insights altogether.

The complicated reality is that it’s possible for a policy to have a tremendously positive impact at an individual level, and yet different impacts at a larger scale. Opposing beliefs can each be partly right and partly wrong.

When ideas don’t mix, this gift of dissonance is lost. Wisdom is lost.

2. Polarization makes our problems increasingly urgent and increasingly unsolvable.

The farther apart we drift, the rarer it is to talk across differences. But by the time a conversation has become unavoidable—a vote is imminent, or a project is underway—the urgency of the situation has made the conflict harder to untangle.

In a paper titled “Motivated Closing of the Mind”, the psychologist Arie Kruglanski notes that our human “need for closure”—our desire for a definite answer to a problem—goes up when we’re stressed, or pressed for time, or when we believe that having a strong opinion makes us look smart. Notice how closely this describes politics and election cycles.

Excessive need for closure, unfortunately, leads to what Kruglanski calls “seizing and freezing”. We grasp for an immediate answer, even when it’s not a great one, and we get stuck there even against countervailing evidence.

I can observe my own “freezing” when I nod along with articles I agree with, but look for logical holes in those that challenge my points of view. This kind of freezing prevents us from finding the wisdom on the other side of complexity.

3. Life demands a capacity for paradoxes.

It’s not easy being human. Our desires are entangled in perplexing opposites. We want to feel freedom and connection; to experience simplicity and complexity; to satisfy curiosity and safety.

These paradoxes aren’t meant to be split apart; each side of a duality is like one bank of a river. Life flows between them.

When we polarize, we split apart our dualities. That’s no way for a society to live. We aren’t meant to agree with each other—we weren’t even made to agree with ourselves. Life is a conversation.

Part 2: The Isolation that Polarizes Us

Many people have analyzed the causes of our political polarization, and I will neither rehash nor dispute these analyses. Our polarization has a complex history.

I hope, though, to add a slightly new take on the question.

At the end of the year-long Between Americans project, I spent an hour on the phone with each participant, glimpsing a tender layer of our nation that wants to know itself better, but that feels stuck.

It’s lonely and frustrating to be in a conversation that’s stuck, so perhaps it’s only natural that many of these final phone calls drifted toward the topic of isolation and loneliness in America.

“I think we’re actually damaging the structure that allows people to be individuals, because now they have to associate with these labels. Are you a Republican or a Democrat? Are you a feminist or not a feminist? And they don’t even come close to touching on the complexity of the actual human…. I think that that creates a sense of isolation and loneliness because here you can name all these containers, but you’re not really known. Nobody actually really knows you.” —Between Americans participant

I could identify with the participants’ struggles to find connection. And when I began to see my own role in the problem, I also began to see myself in a more energizing solution.

First, the problem.

1. I, too, was busy.

“I really enjoyed those first initial conversations, Bo. Unfortunately … it was just at a time when I had started a new job … and I’m a single mom with two kids. Unfortunately, I couldn’t engage in the way that I had hoped.” —Between Americans participant

Many participants blamed themselves for failing to reach out more to the others. In their already busy lives, it was hard to find the time to post something to our group page, let alone to pick up the phone.

I certainly relate to busyness. Workaholism is in my DNA. My dad had grown up in an impoverished farming village; my mom cleaned houses and packaged chicken eggs as the two of them worked their way through grad school in Connecticut. Our family is an American Dream success story.

The American Dream suggests that freedom from vulnerability leads to happiness. But past a certain point, the disconnection caused by that freedom can serve up its own flavor of unhappiness.

“Our lives are spent in a tug-of-war between conflicting desires—we want to stay connected, and we want to be free.” —Jacqueline Olds and Richard Schwartz, The Lonely American

In middle-class America, neighbors each have their own lawn mowers and kitchen stand mixers. We buy insurance policies. We don’t need help.

Self-reliance has a down side, though: we need other ways to know that we’ll be missed when we’re gone.

So I stay busy.

This is not to say that all Americans experience empty busyness. Most of us live paycheck to paycheck and struggle to make ends meet. But I’d long wondered about our growing income inequality—what makes enough not enough for our richest Americans?

In a reversal from a few decades ago, today’s best-educated and best-paid Americans are also more stressed by busyness than the American working class. I mirror this statistic. The more success I’ve found, the busier I’ve become—no longer to make a living, but to feel useful and connected in a self-reliant society where productivity proves that I have a reason to be here at all.

But that busyness also keeps me in silos. When I’m too busy, I contribute to our larger disconnection.

2. I, too, often didn’t know where to begin.

“I hate political discussions…. Even when someone sides on ‘your side’, it seems like they still argue with you on hair-splitting issues, just to be argumentative…. It almost makes me afraid to have an opinion on anything.” —Between Americans participant

I once worked in an office where our leaders never agreed on anything. It was a running joke. But our team thrived on these disagreements. Unless something was on fire, we didn’t feel compelled to end every conversation with a resolution.

Our disagreements forced us to reckon with the competing paradoxes of efficiency, quality, cost, creativity, relationships, and so forth. Difficult conversations challenged us to find a higher synthesis that could resolve competing needs.

But in the trap of political punditry, ideas are either right or wrong. There is no higher synthesis.

When I buy into this trap, I fail to see the point of a conversation that won’t easily end in agreement or a meaningful insight. That also helps grow the schism.

“One of the strongest personal characteristics that any person can have is the ability to be vulnerable. And it’s one of the things that I think as Americans we’re the worst at. We all put on this suit of armor that protects us. And when we talk about politics, and community, and growth, and unity, those suits of armor actually protect us from solving the problems that we have.” —Between Americans participant

3. I, too, believed the Internet.

One short conversation in our Between Americans Facebook group was about environmental issues:

“So I have posted some stuff that’s environmental. And there was actually a lot of thought that went behind that…. I would agonize over what I should post … like, what is something that I [can] talk about meaningfully, without getting too emotional to the point where I can’t talk about it anymore.” —Between Americans participant

Referencing the same conversation, another woman reflected:

“I remember there was one, that someone had written about the environment…. I saved part of the post in my notes and I got back to it later…. And I got a very thoughtful response back…. And then I dropped the ball and I think it was the Fourth of July and I never wrote back. And I was like, ‘Damn … I lost an opportunity to really keep this conversation going and learn about something that I don’t know a lot about.’” —Between Americans participant

Before these phone calls, I’d forgotten how much of our human complexity remains below the surface of the Internet. When we type, our backspaces and pauses—the vulnerable hesitations that connect us as humans—disappear into unwritten words.

And what’s more, the Internet is often a crowd. Crowds carry their own distortion.

At the start of the Cultural Revolution, when my mom was 11 years old, she watched from a crowded plaza as student leaders kicked, hit, and bit her dad’s colleagues in order to force public confessions of academic privilege and oppression. The crowd chanted slogans in support of the class struggle.

When my grandfather took his own turn on stage, my mom slipped away from the square. She quietly avoided future “struggle sessions”. Away from the crowd, she got used to feeling alone.

Only decades later did she begin to hear how uncomfortable others had also been in these public meetings.

What my mom saw—the people, the emotions, the chants—had been real. But here’s the important thing to remember: the larger the crowd, the less evenly it communicates our complex truths.

When I forget that we are deeper than the Internet, I conclude, wrongly, that everyone has gone crazy.

And I retreat even more.

4. I’d found belonging in my political tribe.

Our former surgeon general recently warned:

“The world is suffering from an epidemic of loneliness. If we cannot rebuild strong, authentic social connections, we will continue to splinter apart — in the workplace and in society. Instead of coming together to take on the great challenges before us, we will retreat to our corners, angry, sick, and alone.” —Vivek H. Murthy

As I spoke with friends, and then in public workshops, about the theme of loneliness and isolation that had emerged from Between Americans, it became clear that nearly all of us identified with the feeling. Blessed though we were in social connections and supportive friendships, we could nevertheless spend our days in meetings and lunches and happy hours and not feel as if we’d really talked with anyone.

I began to see how, during the presidential election, real and fake news had exploited a sense of alienation that I hadn’t even acknowledged in myself. Each click and share of an article, every conversation about our side’s heroes and the enemy’s villains, delivered a brief hit of purpose and belonging.

“Humans don’t mind hardship, in fact they thrive on it; what they mind is not feeling necessary. Modern society has perfected the art of making people not feel necessary….

“If war were purely and absolutely bad in every single aspect and toxic in all its effects, it would probably not happen as often as it does. But in addition to all the destruction … war also inspires ancient human virtues of courage, loyalty, and selflessness that can be utterly intoxicating to the people who experience them.” —Sebastian Junger, Tribe

Part 3: Let’s Make Disagreement Great Again

Looking back from the future, I hope we’ll see this time in history not as a struggle between competing ideologies, but rather as an awakening to the complexity of our problems, and a gradual rejection of ideological answers.

My conviction for bridging divides is not about finding peace and harmony, or even common ground. Rather, I believe in talking more so that we can begin to become, perhaps for the first time in American history since colonization, a whole that’s truly greater than the sum of our parts.

Generative, inclusive disagreement isn’t something we need to remember how to do. It’s something we’re learning for the very first time.

As our democracy matures, the very qualities that brought us this close to success—our busyness, our conviction, our production-line innovations—could be the very things that hinder us from moving forward.

Here are some thoughts on how we might heal the disconnection-riddled immune system of our civic body. As always, I’m sharing thoughts in progress, and differing perspectives are welcome.

1. Let’s support a political interview process that rewards learning and dialogue.

Ideologies, unfortunately, depend for survival on appearing to be right. This makes it hard for ideological leaders to learn gracefully.

But our debate-focused election seasons select exactly for rigid ideologies.

Let’s advocate, instead, for campaigns that confront us with our humanity. How does a political leader balance the conviction that’s needed for action, with the openness that’s needed for adapting to new information? What’s their capacity to catalyze collective wisdom in us?

Local Seattle media team The Evergrey acted on this idea during last year’s local elections, resulting in very interesting interviews. More such efforts could go a long way in dismantling our political armoring.

2. Let’s make space for different expressions of truth.

“To give an example of living in a household, if you have a great relationship with everybody in the house, you don’t at that point say, okay, we should stop communicating now, because we have a great relationship. If anything you’ll start communicating more.” —Between Americans participant

Communication takes many forms, and sometimes it travels in disguise.

Silence might mean that someone feels overwhelmed or doesn’t believe that talking will make a difference. Anger hints that someone’s dignity feels under attack. Extremism suggests a fear of powerlessness. Reaching out for a difficult conversation simply means that someone feels safe and hopeful enough to talk.

Healing conversations can only be invited, not coerced. As someone eager to unravel civic puzzles through dialogue, this has been a hard lesson to learn. But only after listening to the silence of Between Americans—and no longer trying to “fix” it—did I hear the truths about our emotional landscape that the silence conveyed.

3. Let’s make space in our own lives.

An economist once foreshadowed the anxiety of productivity that our most self-reliant social classes have fallen into.

“[M]ust we not expect a general ‘nervous breakdown’? … [F]or the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem—how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares….” —John Maynard Keynes, 1930

We can’t have a successful democracy if we’re too stressed out to talk. Let’s support each other in finding some emotional spaciousness wherever possible.

For example, I’m now trying to publish writing only when it feels truly new and useful. This discipline is not easy; it’s forcing me to confront my ego, my embarrassment about not appearing busy enough, and my fear of being useless.

But being respectful of your time is worth it. Helping to lower the volume of the crowded Internet, and accessing my own spaciousness at the same time, is worth it.

4. Let’s organize ourselves to do what we’re actually good at.

“I remember in particular [a participant said] her family comes first, the priority’s there, her job…. And politics is down the list…. And that was fascinating, to get it put in such a plain statement.” –Between Americans participant

Today, political organizing often involves recruiting others to our own opinion. But there’s as much danger of groupthink as there’s hope of insight when we simply propagate our convictions to others.

Further, data show that we citizens aren’t great at picking the best solutions to our problems in the first place. We have too many other things going on.

And what if our toughest political problems are, at their core, problems of isolation and belonging? What if polarization is simply the frustrated result of popping policy pills for an illness that demands a lifestyle change?

“The small group is the unit of transformation.” —Peter Block, Community

I’d once believed grassroots groups to be mere precursors to real political action. But if our civic problems are being exacerbated by polarizing isolation, then these emerging points of light, these local efforts to bridge across differences, are the very lifestyle change we need in order to heal our isolation-infected politics.

Small groups harness what humans are actually good at: survival, belonging, connection, and participation. Our society is longing for an alchemy in which each person’s gifts can feel useful in combination with others.

Having all the answers would be awfully lonely. May we keep seeking opportunities for that alchemy together.

Further Reading

On the present:

- Jacqueline Olds and Richard Schwartz, The Lonely American (excerpt)

- Ijeoma Oluo, So You Want to Talk About Race

- bell hooks, The Will to Change

- Christoper Achen and Larry Bartels, Democracy for Realists (summary)

- Sebastian Junger, Tribe

On the future:

- Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging (related principles)

- Alex Pentland, Social Physics

- William Isaacs, Dialogue: The Art of Thinking Together (summary)

- Frederic Laloux, Reinventing Organizations (summary)

- George Monbiot, Out of the Wreckage

Leave a Reply