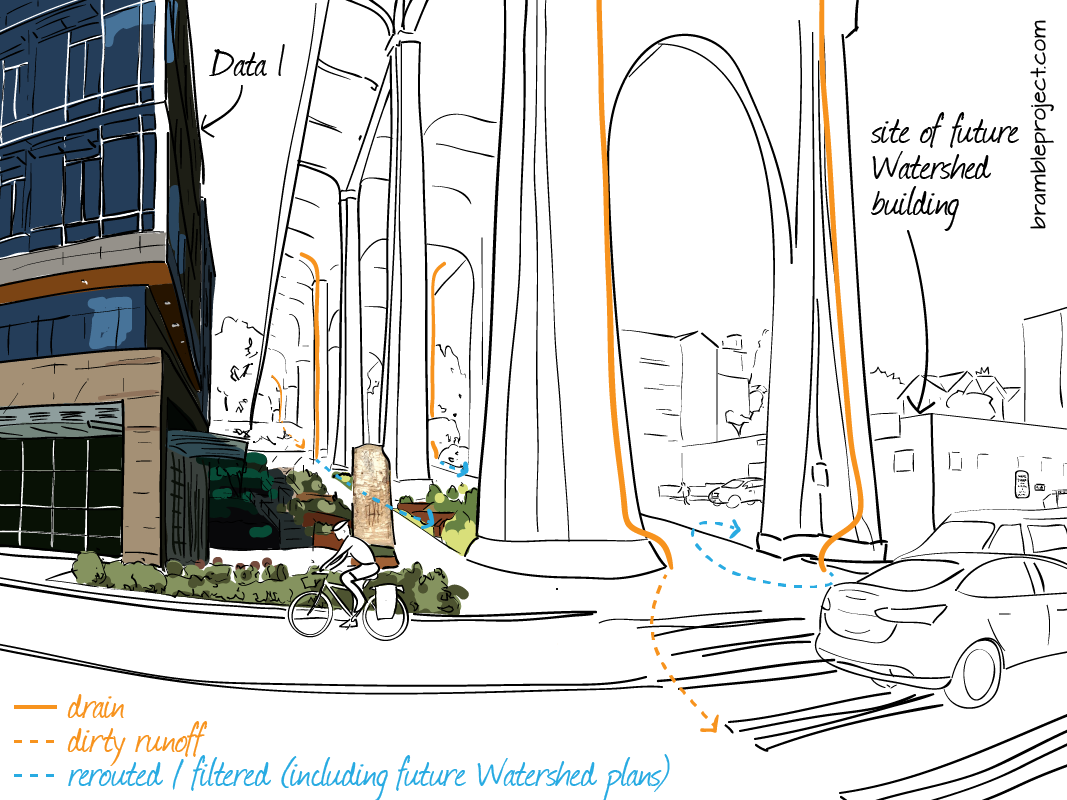

Why would developers voluntarily clean up icky runoff from the Aurora Bridge?

In Fremont, a block uphill from Seattle’s ship canal, construction is wrapping up on a glassy office building. An unassuming, newly landscaped terrace flanks the building. The Aurora Bridge soars above the terrace, carrying cars over the canal.

Along the canal, boats dot the water’s surface on this sunny July day. Below the surface, salmon have begun their migration upstream. The salmon run will continue into the winter, and their babies will make the return trip to the ocean come spring.

The Mystery of the Murderous Runoff

Among the survival challenges the salmon face is stormwater runoff from the bridge. When researchers submerge salmon in this dirty rainwater, even adult fish die quickly.

Scientists haven’t yet been able to replicate the toxic cocktail in a lab—simply mixing the known toxins in runoff doesn’t kill fish the way that real runoff does. Despite the mysterious nature of this toxicity, simply passing runoff through gravel and soil cleans the water enough to keep the fish alive.

When developer Mark Grey saw a video in 2014 of salmon dying in toxic highway bridge runoff, he emailed his development partners. Could they do something with their planned developments to help filter the runoff from the Aurora Bridge?

Development and Stormwater

Bioswales, or swales, are landscapes that slow down stormwater, filtering the water as it trickles through. CoU—the development partnership of Mark Grey, Mike Hess, and Joanna Callahan—aren’t the first private developers in Seattle to build swales in their projects.

Vulcan, the large local development firm responsible for many new buildings in the tech-centric South Lake Union neighborhood, is partnering with Seattle Public Utilities to build the Swale on Yale, a multi-block stormwater treatment effort.

Greenfire, a residential/office campus in the Ballard neighborhood built on the theme of sustainability, brought landscaped rainwater filtration and bird habitat to a site that was once mostly asphalted parking.

And yet, Data 1 and Watershed—CoU’s two planned buildings in Fremont—seem unprecedented. Like Vulcan, CoU is treating dirty stormwater outside of project boundaries. Like Greenfire, the project is entirely voluntary and privately funded. CoU managed to hit both marks.

The Hometown Connection

It’s hard to live in Seattle and not develop a love for the water. Mike was crew Captain while studying at the University of Washington. His daughter Joanna rowed at Yale.

In her first ever learn-to-row class, Jo took a swim test right where the Aurora Bridge drains into the canal. “The water coming out of the downspout is pretty nasty,” she says. “And then you realize that’s what we were swimming in.”

The Market for Sustainable Office Buildings

CoU’s name refers to Center of the Universe, a long-standing moniker thfor the historically arts-centric Fremont neighborhood.

The Artistic Republic of Fremont is hereby declared, decreed, and determined to be an Independent ImagiNation and a Mecca for those of independent minds and spirits, and is forever and fervently empowered with all the rights and privileges thereto accruing. Further, the Metropolitan King County Council plainly postulates and proclaims Fremont to be Center of the Universe….

—Proclamation at Metropolitan King County Council meeting, July 25, 1994 1

These days, downtown Fremont is also home to many tech offices. “Tech tenants value design and sustainability,” notes Jo. “So, really, we’re chasing the market.” As I’ve noted previously, the more conscientious the market, the more conscientious the developments. And Tableau, as CoU’s “market”, has a history of working to integrate thoughtfully into the Fremont community.

Stumbling upon the Investment Value of Thoughtful Development

Mike and Mark’s first green building, the Terry Thomas, also had its ethics driven by an intended tenant, architecture firm Weber Thompson—who has gone on to design the buildings in Fremont.

The team finished the building in 2008, just as the Seattle commercial market tanked. Employers shrank in size. Despite the dizzying economic downturn, Mike and Mark managed to find new tenants to keep the building occupied. And in 2008, just maintaining occupancy put them in better shape than most property owners.

“It just feels like a nice building to be in,” says Jo, who joined the other partners as Seattle was climbing out of the recession in 2011. “For us, it was a big lesson in realizing that it’s not just dollars and cents for tenants.”

Getting ’er Done

Coordinating the new swales in Fremont was surprisingly tricky. The Aurora Bridge—Highway 99—is owned by the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT). Runoff from the bridge, however, drains onto city-owned property (SDOT). Building the swale required coordinating with both bureaucracies.

“Once [staff] realized what we wanted to do and that we were genuine about it, they got on board. But there’s this initial response—that if it’s never been done, there’s probably a reason. There also isn’t one clear person who has the authority to tell these crazy developers that their project is okay.”

Financing

Though CoU tried to get public funding for the swale, they ended up footing the full cost. “We actually never broke out the cost of the swale separately from the rest of the landscaping,” says Jo, “I think partly to protect it from VE.”

“Getting people to appreciate the value of sustainability takes time,” says Jo. “Your return is usually biggest if you flip a project right away. We don’t intend to sell this building. But how do you get more developers to think long-term? I don’t quite know what the answer is.”

A Sense of Meaning

“What I love about the bioswales,” says Jo, “is that I think they’re going to be really cool to walk through. It’s not just going to be about treating the water, but also having people learn about how the water is treated.

“I’m also proud that we have 100% local tenants, and that we made sure the retail matches the community.”

Two beloved local shops, Cafe Turko and Milstead & Co. coffee, had lived at the site of Data 1. To keep them in business, CoU temporarily moved them next door, retrofitting a kitchen and outdoor dining deck for Cafe Turko.

Both businesses will move back to Data 1 once it’s complete—though Cafe Turko will have a hard time giving up its sunny deck, a new but temporary luxury.

“National retailers probably would have paid more in rent, so there are some decisions we made that probably weren’t about the bottom line,” notes Jo. “But hopefully long-term it’s good for our reputation, to be developers who care and follow through on our word. And I think Tableau cares too.”

And that’s what I think we can realistically strive for—not for developers to do charity work, but simply for them to hold a more enlightened definition of self-interest.

Being Good Neighbors in a Growing City

As just the third building in eight years to strive for Seattle’s Living Building pilot program, Watershed will qualify for an extra floor, rising to seven stories. Between the bridge and the six-story St. James Tower Apartments, that likely won’t seem out of scale.

But, inevitably, the building will block views for Waterford Place residents just uphill. The development team sat with Waterford’s homeowner’s association for two hours, addressing concerns.

“It was really good to talk to them,” recalls Jo. “You have in your mind what their concerns would be, but you sit down and realize that it’s totally different. For example, the architect had thought that privacy would be a big concern, and designed skinny windows on that side so it would feel more private. It turned out they wanted to see more windows.” As a result of the conversation, condo residents will also be looking at a green wall.

The Impact of Design Review

Because Seattle’s permitting process requires at least two public design review meetings, during which the community is invited to comment, we can trace the progress of a developer’s neighborhood outreach. Wrote one Neighborhood Council representative at the end of the public process for Watershed:

“The team has … presented the project at two public Neighborhood Council meetings to gather community input, advice and concerns. They also met with members of the condo building directly to the north of the project and asked for their input. Concerns which have all been addressed in the plan….

During my service on the Fremont Neighborhood Council board, we have rarely encountered a developer and design team that has been as committed as this team has been to ‘getting it right’.”

More on how the design review process influences development, for better and for worse, in a future post.

Notes:

- Thanks to The Fremocentrist for helping dig up this piece of history!

Leave a Reply