Can a single design- and environmentally-conscious developer influence others?

Tim McDonald runs Onion Flats with his three partners. Trained as an architect, Tim co-founded the Philadelphia-based design-build firm alongside his brother. “As a developer,” he says, “every project I’ve ever done has been an opportunity to explore something. I’m a design-driven developer, and I come at it from an architect’s perspective.”

As as Northern Liberties Zoning Committee Member

Tim’s a longtime member of the Northern Liberties Neighbors Association (NLNA) Zoning Committee, so I begin by asking: What’s it like to work with other developers, while in your role as a community member?

Good Bart, Bad Bart

To answer my question, Tim tells the story of Bart Blatstein, another local developer who’s sometimes described as two people in one: Good Bart and Bad Bart. Tim puts it this way: “Good Bart understood the importance of good design, hired the right people, built the project the right way, and dealt with the community on a good basis. Bad Bart would bang shit out and didn’t care.”

When Bart was developing what’s now called The Schmidt’s Commons, the community had leverage: the power of the variance. Northern Liberties at the time had been zoned industrial, so Bart needed approval to build apartments.

To get this approval, Bart met repeatedly with the NLNA Zoning Committee over several months.

“Every time we met we’d just throw stuff at him. Here’s a mixed-use community in Germany, Seattle, California … he really needed to be educated about what was possible.

“Then he took a trip to Italy and discovered piazzas and came back like a little kid, totally excited!

Putting the Italy in Philadelphitaly

“He hired a horrible architect and brought this plan that he called The Piazza to the neighborhood. Frankly, it’s essentially what’s built now, but it was a fake Neoclassical stuccoed Italian piazza. So we were like, ‘OK … not a parking lot … awesome … let’s get to work.’

“So we just started bringing designs.

“Eventually I took his elevation home, and kept all the windows exactly the same, and I did these 3-4 different schemes playing with materials and proportions. And I just kind of threw them down. Now, every time I did this he was kind of pissed off.”

The fascinating story of what happened next is detailed in this 2004 article (halfway through, under “Blatstein Gets Religion”) and worth reading in its entirety. But in short, Bart un-crumpled one of Tim’s drawings after he got home. He then dialed Tim’s number. Eventually, in Bart’s own words, he “got religion”.

Tim continues the story. “He started hiring good architects and doing good work. He was still a pain in the ass, don’t get me wrong—we fought for every single thing. But that was the moment where he got a holistic understanding of what he was doing. Not just uses, but how things met the ground, the types of retail. I gotta say, he’s done well.”

Onion Flats’ Evolving Purpose

“In my early years,” Tim says, “I was a big fan of the relationship between thinking and making. We designed stuff on the fly all the time. The intent was to draw as little as possible and let the site be a part of the creative process. The folks on my team loved this more intuitive way of working, and I gave them lots of leeway…. We get shit done, but we have so much fun doing it.

“But then I got really, really, really passionate about sustainability, and then high-performance buildings. And so now for me, what brings me joy is knowing that I’m taking on what I believe is the ‘new gravity’ for our time—greenhouse gas emissions and global warming.”

Climage Change: The New Gravity

By “new gravity”, Tim means that climate change should constrain architecture as much as gravity does. “Did you know that buildings are responsible for almost half of the issue? That should shock and motivate every architect, student, and professor.”

“I’ve always tried to demonstrate what’s possible. I used to think, if I can demonstrate to other developers that you can do good design, and show them pro formas and show they can do it too, then I could change what development looks like. It’s not true. They don’t give a shit.” I’m more than a little deflated by Tim’s hard-earned epiphany.

Tim continues. “I realized, I can’t make a difference one building at a time. I’ve got to think about how we scale this position.”

Mission Net Zero

“We have to design net-zero-energy buildings as a baseline. Period. Now. Not in a generation. All the other stuff about materiality and design is still there, but the joy for me now is knowing that the building we’re doing right now is the largest net-zero-energy building that we’ve ever done. It’s really a prototype that we’re going to repeat in other contexts for the next five years. And I want to make that on a much larger scale across the country.”

Onion Flats through the Years: West Laurel Street

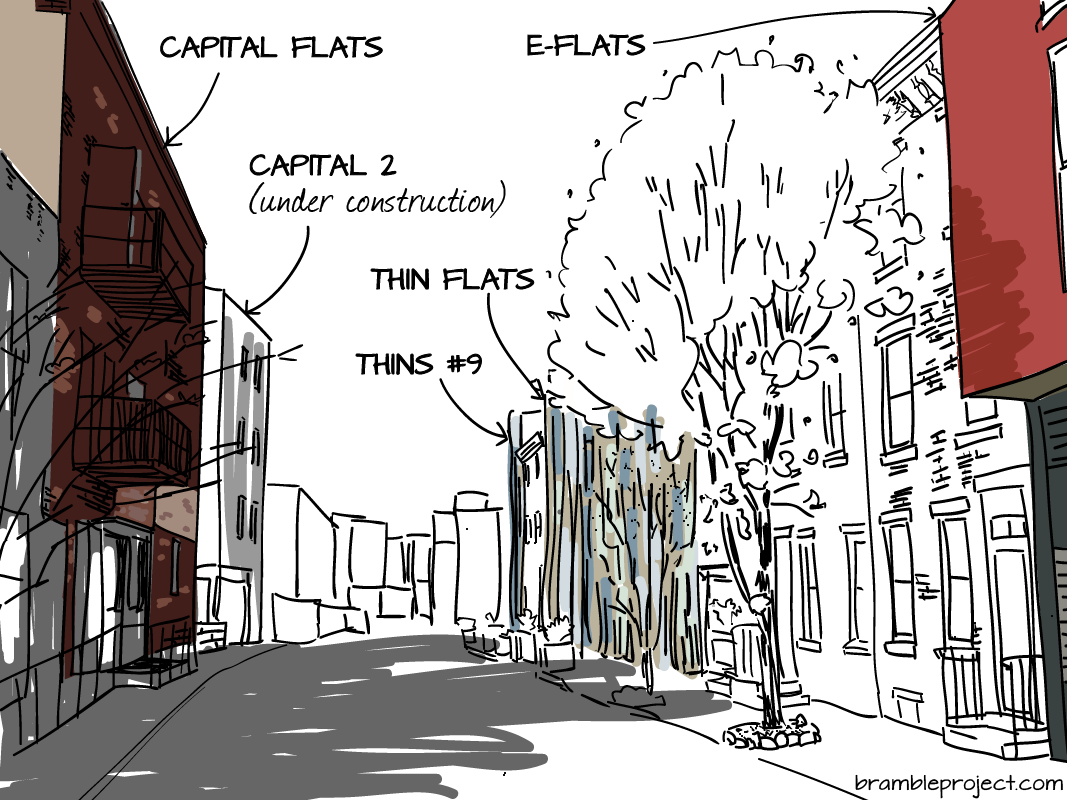

For more on the evolution of Onion Flats’ thinking, check out their own descriptions of four neighboring projects—Capital 1 in 2002, Thin Flats in 2009, Thins Number 9 in 2010, and Capital 2 under construction. Photos provided to Arch Daily of Capital 1 and of Thin Flats reflect the deeply unique outcomes of designing on the fly.

Financing

Onion Flats brings in their own equity. These days, banks often let them count the land toward the equity needed for loans. “We’ve tried to go the other direction—get bigger, bring on partners and investors,” Tim says, laughing. “Life’s too short.” Too much brain damage, I ask? “I love designing and building things,” he answers.

From Onion Flats’ beginnings in 1997 in Old City, they have needed to stay a step ahead of larger developers. “Our approach to development from Day 1 was always, go where people aren’t,” says Tim. “We knew that we weren’t seasoned enough developers. We were going to make mistakes.”

Gentrification

A cost of beautiful design is that it can drive up the market in the neighborhood. Tim takes a pessimistic view on gentrification. “As soon as gentrification began to happen, we moved to the next neighborhood. That was our way of being able to do the experimental work that we wanted to do.”

What have they done to mitigate gentrification in Northern Liberties? “My basic understanding of gentrification is you can’t avoid it,” he says. Tim then refers to their current Capital 2 project, which consists of smaller 1-bedroom apartments averaging under 600sf, together with a small handfull of 2-bedroom units. The building consumes net zero energy, which will reduce living expenses. “That’s our approach, in terms of what we can do as market-rate developers to keep a different demographic in a neighborhood that’s very quickly pushing anybody out.”

Gentrification in Northern Liberties

The role of developers in gentrification is something that we at Bramble will likely always grapple with. It’s a particularly challenging aspect of writing about cities that we don’t know as well as we know Seattle. This Pew report (p. 20-22) provides some context, saying:

Given the relatively small population in Northern Liberties before gentrification, and the fact that much of the growth took place in areas that had not been residential, less controversy regarding development has occurred there than in other neighborhoods. But some concerns persist, particularly about the loss of a diverse working-class community that had been home to Puerto Ricans, African-Americans, and immigrants—and of the neighborhood’s artistic identity.

The Pew’s use of pie charts obscures population numbers, so here’s the same data shown as a bar graph.

Economic Development vs. Community Stability

Overall, I was surprised by how many vacant buildings there continue to be in Philadelphia. The city’s population has grown in recent years to 1.5 million, which is still only 75% of the population in Philadelphia’s heyday of the 1950s. Perhaps this is why the city seems to be spending less time wringing its hands about displacement than Seattle is—it still seems afraid to slow the momentum of growth.

Therein lies the dilemma. By the time growth feels unstoppable, gentrification usually feels unstoppable as well.

In the near future, we’ll share our current thoughts on the role of developers in gentrification. This is obviously an evolving dialogue, and we look forward to hearing your thoughts on the matter.

Leave a Reply