Why is it so hard to find developer success stories in combating gentrification?

In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith explored the cultural milieu that produces our sense of right and wrong. In this work, which laid the groundwork for The Wealth of Nations, Smith notes that it’s human nature to seek praise and praise-worthiness. This basic tendency, he supposes, forms a social glue that keeps our societies ticking along.

He who coined “the invisible hand of the market” in fact seemed to view morality and markets as complementary, not competing, forces. How might this perspective apply to urban development?

The Culture of Praise-worthiness

As long as developers consider it praiseworthy to provide the highest legally permissible returns for investors—and continue to excuse each other for choices that might be called “not so thoughtful, but definitely legal”—we expect that real estate development will continue to demand stiff regulation.

If the industry can evolve beyond that limited understanding of self-interest, we might free ourselves to be more creative than the highly regulated box that we’ve drawn ourselves into.

In future posts, we’ll expand upon why we think it’s in the industry’s self-interest to evolve. For now, let’s talk about what an industry conscience might look like.

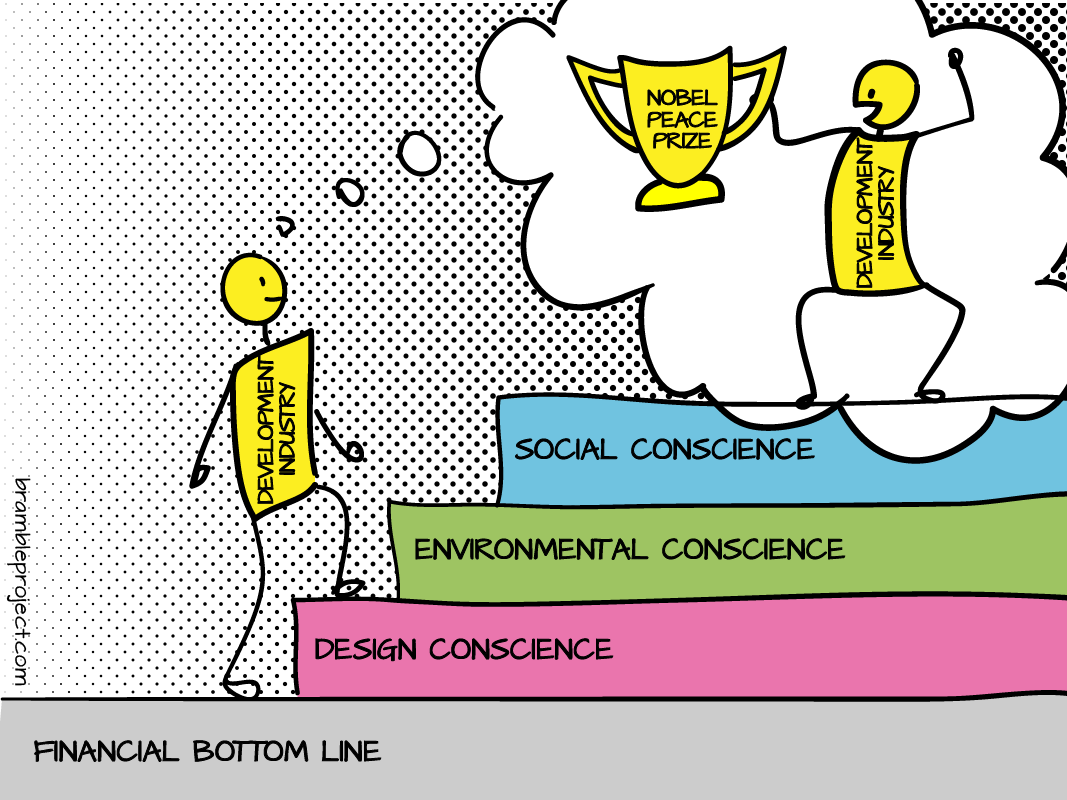

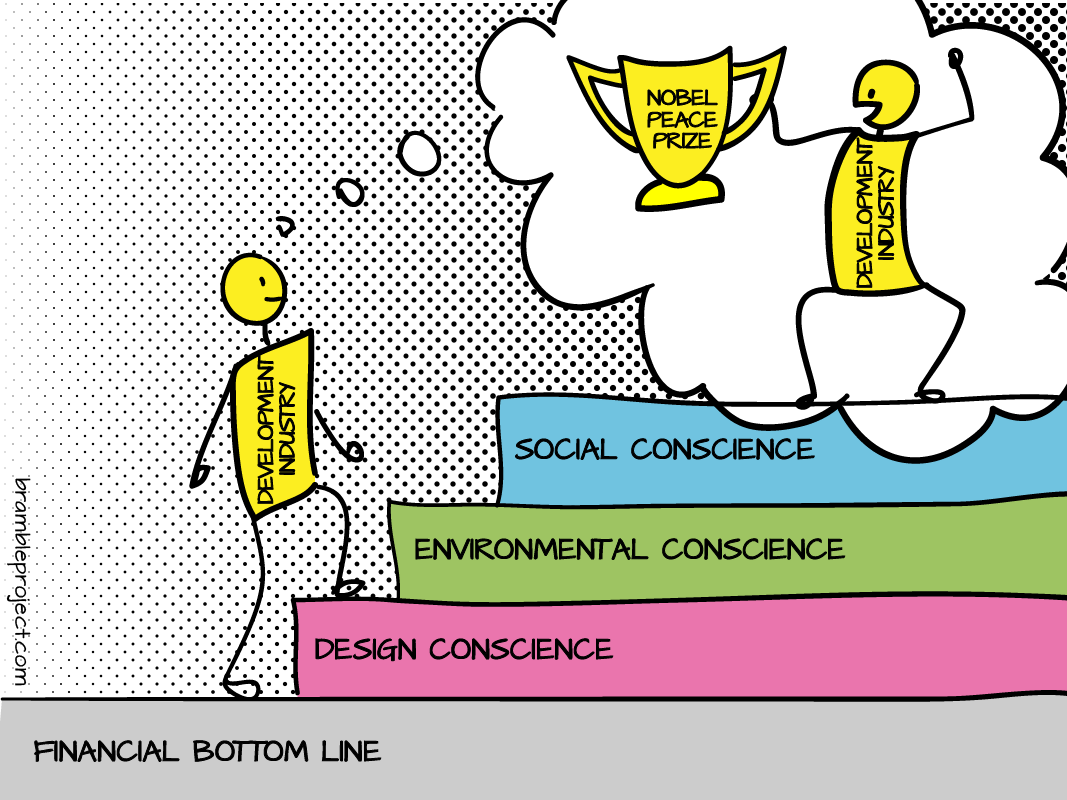

The Hierarchy of Praise-worthiness

We know quite a few developers who want to build or preserve beautiful buildings. We’ve found fewer who focus on building to environmentally sustainable standards. And we only know a small handful of private developers who are focused on social needs such as affordability, racial equity, or even simply maintaining a connected community.

This leads us to suggest that there’s a hierarchy of developer conscience, summarized below.

Improvements over Pure Financial Motivation

Many urbanists, such as Edward Glaeser, argue that dense urban development is good by its very nature. They describe community as a sort of ubiquitous moss that can grow anywhere: yesterday’s insipid new tower is today’s thriving hub, and will age into tomorrow’s affordable real estate. By this view, developers should be free to build without judgment. After all, with time, even the most soulless building will be filled in with the moss of a thriving community.

This strikes us as over-confident. Brian and I are less optimistic that mass urban exodus is safely a thing of the past. If tedious architecture takes over cities, we suspect that the next generation will seek alternatives. And what a waste of our collective efforts that would be.

Thus, we think it’s important to point out that having a design conscience is good for cities. Design makes it likelier that our rediscovered love of cities will last for more than a generation.

Conscience vs. Supply

To be fair, the urbanist argument for building quickly is intended to meet another critical aspect of thriving cities: affordability. We have so much to say on this matter that we’ll need to save it for multiple future posts. Watch this space.

Possible Reasons for the Hierarchy

So why do we expect the development industry—if it gets religion—to first rally around design, then the environment, and only finally around social goals? Given what we’ve observed so far of the number of give-a-damn developers in each space, we suggest two possible factors: perceived cost, and perceived pathways toward making a dent in the ultimate goal. Both perceptions can be changed.

Perceived Cost

Many design-driven developers go out of their way to point out that they’re making smart investments. Many have been able to show that people are willing to pay more to live and work in beautiful buildings.

Environmentally sustainable buildings also seem very doable. In many cases, investors can recover the extra cost of building green features, through rent premiums or savings in utility costs.

However, most developers still view affordability and community stewardship as a net drain on financial resources. We’ve heard of just a few private developers who see things differently. To them, diverse communities are richly rewarding resources, and it pays to steward them. We’re excited to explore their projects in future posts. In the meantime, since development culture won’t shift overnight, we’ll still need policies and subsidies to preserve the social fabric of fragile neighborhoods.

Perceived Progress toward the Goal

Many design-oriented developers used to be architects, and simply got tired of working for someone else. The career path from wanting to live in a beautiful city, to wanting to develop and preserve beautiful buildings, is clear.

Objectively, tackling climate change is just as daunting as tackling social inequity. However, as a culture, we’ve overcome our sense of individual insignificance on this issue. Our social norms are now to recycle, compost, and scold folks who litter. We’re awakened to the collective difference that we can make through small individual choices, and we aren’t paralyzed by perfection.

I hope we’ll see a similar cultural shift in the social justice sphere. Currently, the perception of individual insignificance still dominates. Activists thus continue to focus on policy improvements rather than behavioral shifts.

Toward More Social Conscience

Perhaps someday, with increased awareness, better-off residents will choose to pay more to live in mixed-income buildings. Or maybe we’ll develop a cultural taboo against moving to places where lower-income renters or businesses are being involuntarily priced out. Until then, gentrification will continue, and it won’t entirely be the fault of developers—it’ll be the market’s fault, too.

Right now, with private developers and capitalism perceived as the drivers of gentrification, most socially-minded developers remain in the non-profit space. This is a huge loss. We think there’s significant room for creative minds to make inspiring, potentially industry-shifting moves in the space of socially-minded private development.

Further Reading

The Theory of Moral Sentiments is quite dense to wade through. Admittedly, I’ve read far more about it than I’ve independently parsed within it. For a very accessible summary, check out How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life. Its author, Russ Roberts, hosts the EconTalk podcast, which has devoted quite a few episodes to the morality lens of Adam Smith’s work.

Leave a Reply